1. What is continuity? What is discontinuity?

With functions in real life, we deal with both continuity and discontinuity. Continuous graphs entail of many characteristics: predictability (meaning you are able to know where the graph is going), the lack of breaks, holes, and jumps (because it is CONTINUOUS), and the ability to be drawn without lifting your pencil. Knowing this, we can also note that in a continuous graph, all limits should be equivalent to its values (if this is not completely understood, it will be clearer with further information). Basically, continuity is seen in many of the graphs dealt with in earlier years of math (in regular parabolas, linear graphs, etc).

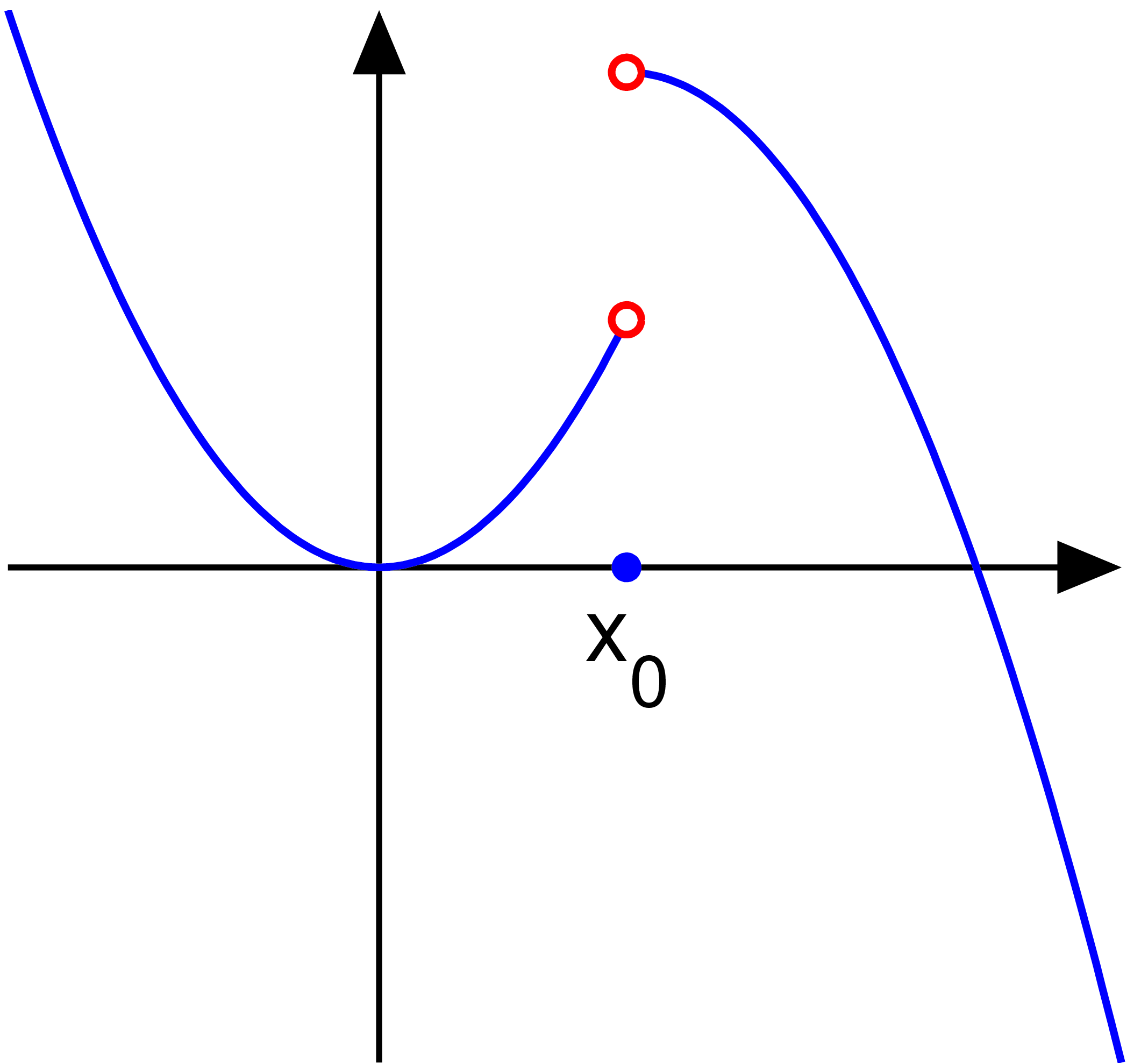

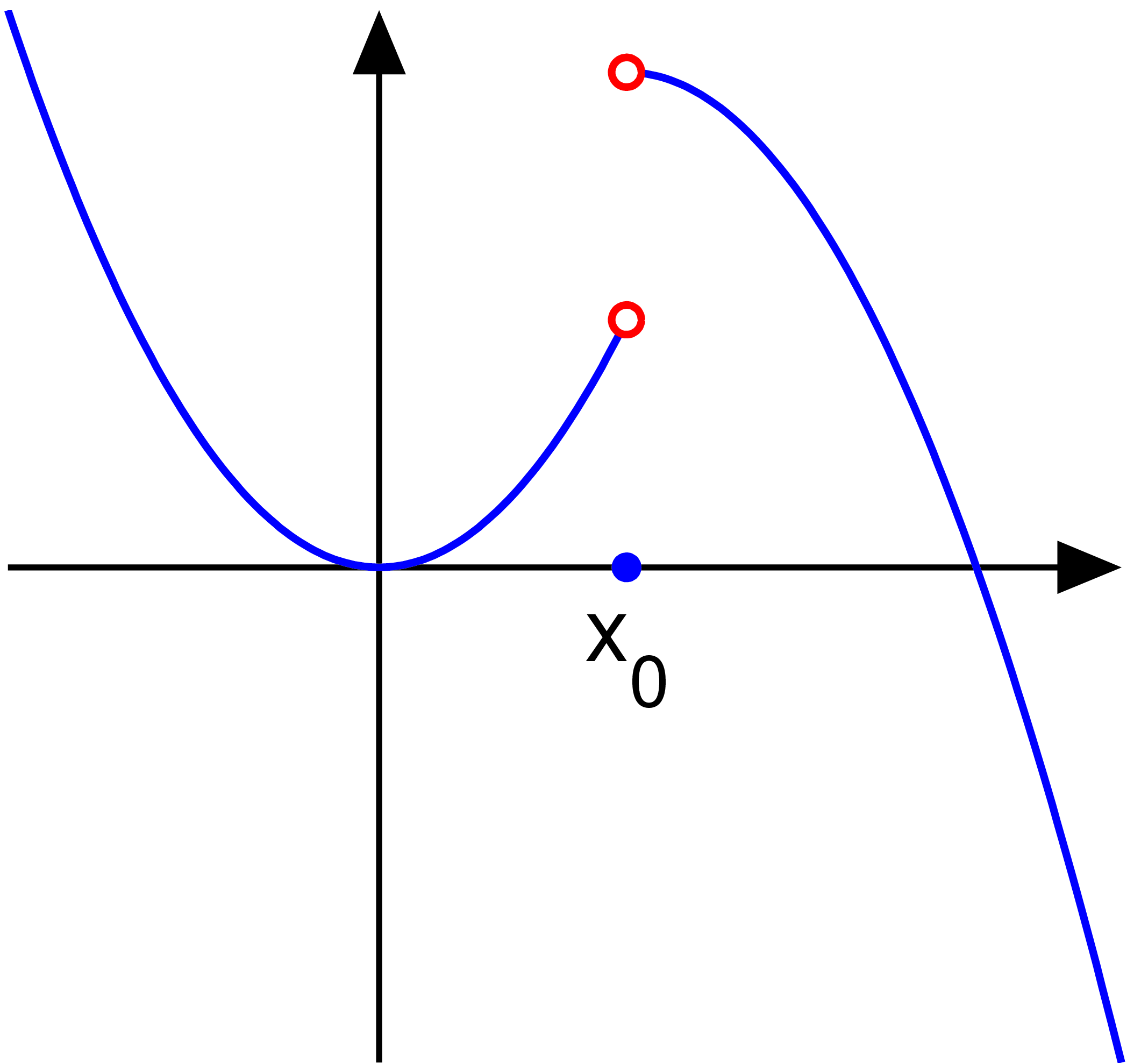

Discontinuity is the opposite, as you can already guess. Discontinuous graphs have breaks, jumps, and holes, meaning you WILL need to lift your pencil from the paper in order to draw these graphs. There are four specific discontinuities found in these types of graphs. The four discontinuities branch into two categories: removable and non-removable. The only discontinuity that is removable is a point discontinuity. These occur when we have a hole in the graph.

|

| Point Discontinuity (http://dj1hlxw0wr920.cloudfront.net/userfiles/wyzfiles/4a69dec7-03e0-492f-ac16-4dcd555579c9.gif) |

There are three non-removable discontinuities: jump discontinuity, oscillating behavior, and infinite discontinuity. Jump discontinuities occur when our left and right limits do not match. Look at the picture below to understand this better.

|

| Jump Discontinuity (http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e6/Discontinuity_jump.eps.png) |

Oscillating behavior occurs wherever you see "wiggles".

|

| Oscillating behavior (http://webpages.charter.net/mwhitneyshhs/calculus/limits/limit-graph8.jpg) |

Infinite discontinuity occurs when a vertical asymptote is present which leads to unbounded behavior.

|

| Infinite Discontinuity (http://dj1hlxw0wr920.cloudfront.net/userfiles/wyzfiles/44bad38c-431e-4382-8fe9-86303561b2a0.gif) |

2. What is a limit? When does a limit exist/not exist? What is the difference between a limit and a value?

A limit is the intended height of the graph. Think of it as where the left and right are intended to meet. You and your friend are meeting at a diner but come from different ways. As long as the two sides meet, your limit exists. Let's go further into this. We now know what a limit is but where does the limit exist and where does it not.

I mentioned briefly in the section above about limits. In continuous graphs, the limit always exists because the graph continuously intends to reach the same point. Let's go into our discontinuities again. Looking back at the point discontinuity, understand that our limit does exist here despite the hole present. Remember, a limit is the INTENDED height, meaning we intended to get there. A hole marks the place that we intended to get to. Think of it like you and your friend tried to meet at the diner but the diner moved somewhere else. You two still should have ended up at the same place.

Now, sometimes...

|

| I'm sorry, I had to. (http://media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m1eqlrQcTf1qdt09k.gif) |

The limit does not exist at those three non-removable discontinuities we discussed earlier. The question though is why? The limit does not exist at a jump discontinuity because we have different left, right limits, as I said before. When I say this, I mean that the left and right sides of the function just don't match up; they do not meet the same INTENDED height. It is as if you and your friend went to two different diners, you didn't meet up with each other. With jump discontinuities, because the limit does not exist, we have side limits, our left and right limits that I mentioned before. These side limits look practically the same as our limit notation (the limit as x approaches a # of f(x) is equal to L)

(http://webpages.charter.net/mwhitneyshhs/calculus/limits/limit01.jpg). The only difference is that our side limits have a (+) and (-) next to that c, our number. A c- is from the left limit; a c+ is from the right limit.

|

| One Sided Limits (right limit, top; left limit, bottom) (http://www.vias.org/calculus/img/03_continuous_functions-69.gif) |

Moving on, the limit does not exist when dealing with oscillating behavior. It is practically impossible to actually see the limit of this graph (because of so many wiggles). Truthfully, it does not approach a single value.

Finally, the limit does not exist when we have an infinite discontinuity. As stated before, this discontinuity exists when we have a vertical asymptote which leads to unbounded behavior. This basically means that it is approaching infinity but really, we can never approach infinity because it is not an actual numerical value. That is why our limit does not exist.

Just to clarify as well, we understood earlier that a limit is the INTENDED height of a function. Therefore, it is good to know that the value is the ACTUAL height of a function.

|

| (http://dj1hlxw0wr920.cloudfront.net/userfiles/wyzfiles/4a69dec7-03e0-492f-ac16-4dcd555579c9.gif) |

I used this picture below but it provides a good example of a limit and a value that are different. The hole in the graph is our limit. Why? Take your fingers and place one to the left and one to the right of the graph. Inch them closer and closer to one another. Notice how they INTEND to reach the hole. They intend to reach that hole, therefore, that is our limit. However, above that hole, we have an actual point, our VALUE because it is the ACTUAL height of the function.

I mentioned this before though, our limit and value are not always different. In continuous graphs, our point where we intend to reach (the limit) is also the actual value of the graph.

3. How do we evaluate limits numerically, graphically, and algebraically?

We use tables to evaluate limits numerically. We take a limit and find x values that approach it and find out. You want to find 3 values to the left of the value and 3 to the right. From there, you would trace these x values (in your graphing calculator) and find the y value. By finding the y values you should notice whether or not they are approaching each other towards a common limit or not. For better understanding, watch the video below, as they go over it more in depth.

Graphically, we take our left and right finger and basically trace ourselves. We first plug our function into the y=screen of our graphing calculator. Then, we go to GRAPH and we TRACE. We trace to the value we are looking for basically.

Sometimes, we are actually given a graph. If this occurs, you place your figners to the left and right of where you want to evaluate a limit. Wherever your fingers meet, you have a limit. If they do not meet, your limit does not exist. The video below shows better visual for this process.

Finally, we can evaluate limits algebraically. There are three ways to do this; direct substitution, dividing/ factoring out, and rationalizing/ conjugate.

Direct substituion is where we basically take the x value that we are approaching and plug it into the function. There are four possibilities. You could end up with a numerical answer, 0/# (still 0), #/0 (undefined, which means the limit does not exist), and 0/0 which is indeterminate form. If you ever get indeterminate form, you use another method.

The dividing out/ factoring method is used when we get indeterminate form. What we do here is factor what we can. If you get x^2-9 you factor that into (x-3)(x+3), and other things of that sort (sum and difference of cubes will pop up as well). If factored correctly, you should be able to cancel something out. After canceling out terms, you should be left with a simpler function. Plug in the number that you are approaching and you should get your answer.

Rationalizing/ conjugate method is used if you cannot factor out--most likely, you have a radical. All you need to do is multiply the entire fraction by the conjugate. You take the conjugate of the term that has the radical. (If you do not know what the conjugate is, it is basically changing it from say this: 3x+1 to this: 3x-1. You just change the sign). You should be able to cancel terms out after FOILing. Plug the number into the simplified problem and you get your answer.

In the video below, they go over examples of the three ways to algebraically solve limits. (The video is a little shaky, but the content is there).

References:

1.http://dj1hlxw0wr920.cloudfront.net/userfiles/wyzfiles/4a69dec7-03e0-492f-ac16-4dcd555579c9.gif

2. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e6/Discontinuity_jump.eps.png

3. http://webpages.charter.net/mwhitneyshhs/calculus/limits/limit-graph8.jpg

4. http://dj1hlxw0wr920.cloudfront.net/userfiles/wyzfiles/44bad38c-431e-4382-8fe9-86303561b2a0.gif

5. http://media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m1eqlrQcTf1qdt09k.gif

6. http://webpages.charter.net/mwhitneyshhs/calculus/limits/limit01.jpg

7. http://www.vias.org/calculus/img/03_continuous_functions-69.gif

8. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8z4aofW85K4

9. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVcqrDFcaCA

10. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CvB4080WC48

(http://webpages.charter.net/mwhitneyshhs/calculus/limits/limit01.jpg). The only difference is that our side limits have a (+) and (-) next to that c, our number. A c- is from the left limit; a c+ is from the right limit.

(http://webpages.charter.net/mwhitneyshhs/calculus/limits/limit01.jpg). The only difference is that our side limits have a (+) and (-) next to that c, our number. A c- is from the left limit; a c+ is from the right limit.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)